Resolver el doble gasto. Por Craig Wright

Resolver el doble gasto

Por Craig Wright | 08 ago 2022 |

Proponemos una solución al problema del doble gasto utilizando una red peer-to-peer…

La solución al problema del doble gasto implica más que simplemente darse cuenta de que se realizó un intento de ataque; requería que el sistema pudiera ser rastreado (Lee et al., 2003). Bitcoin transmite cada transacción y cada intento de transacción a cada nodo (Wright, 2008, p. 3). Tal requisito es el primer paso para ejecutar un nodo; para que un nodo de red funcione, debe asegurarse de que «las nuevas transacciones se transmiten a todos los nodos». Si bien los nodos no requieren que se encuentre una transacción de inmediato, el propósito principal de los nodos de Bitcoin es actuar como un «servidor de marca de tiempo para generar una prueba computacional del orden cronológico de las transacciones» (Wright, 2008, p. 1).

Brands (1994) discutió la capacidad de integrar la trazabilidad del doble gasto en esquemas de firma ciega. El autor señaló que las protecciones contra el doble gasto “pueden lograrse trivialmente en sistemas con total trazabilidad de los pagos” (Brands, 1994, p. 1). Sin embargo, se argumentó que la introducción de la trazabilidad “requeriría un gran sacrificio en eficiencia o parecería tener una seguridad cuestionable, si no ambas cosas”. Al mismo tiempo, el requisito de abordar el problema del doble gasto no exige que todos los participantes en la red vean todas las transacciones.

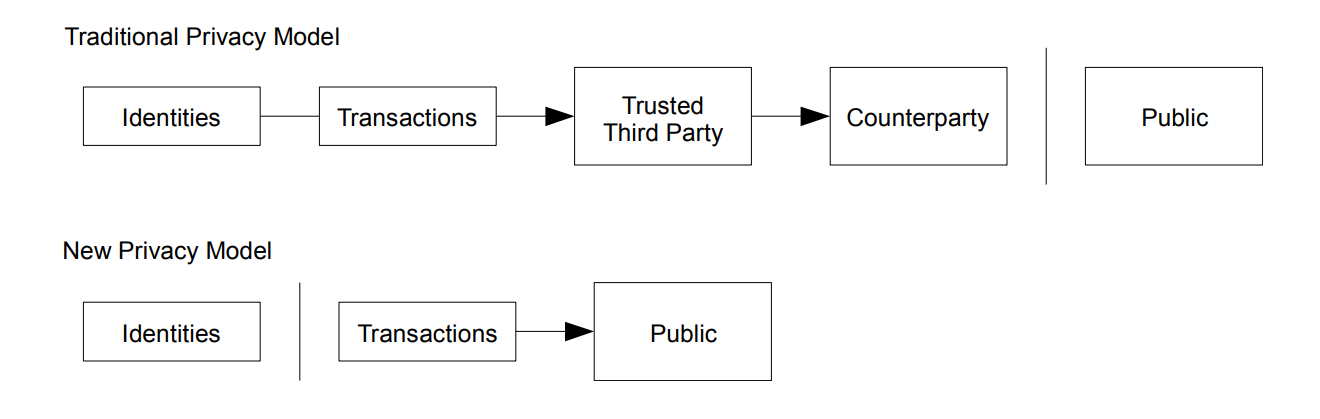

El problema que señala Brands (1994) está asociado con los esquemas de firma ciega para la privacidad. Implementar un sistema diseñado para no reutilizar claves y poder formar pares de claves privadas en base a las propiedades ECDH asociadas a ECDSA (Wright & Savanah, 2022) permite solucionar el problema del doble gasto. Al requerir nuevas claves derivadas de una clave maestra, se mantiene la privacidad mientras se vincula la identidad. Dado que los participantes en una transacción pueden crear nuevas claves de forma segura sin interactuar, basándose en información como las claves de identidad basadas en PKI, se puede mantener la privacidad entre las personas mientras transmiten información a los observadores.

Ferguson (1994) amplió un esquema de efectivo electrónico anterior para permitir que las monedas se gastaran varias veces. El sistema incorporó observadores al protocolo. Al hacer que las entidades validaran y observaran las transacciones, el proceso permitió capturar y detener el doble gasto o, en el peor de los casos, encontrarlo y rastrearlo después del evento. Por ejemplo, Ferguson (1994, p. 296) explicó que cuando dos partes, Alice y Bob, están realizando transacciones, «no existe una forma criptográfica en la que podamos evitar que Alice gaste la misma moneda dos veces en un sistema fuera de línea». Aquí, agregar observadores hace posible monitorear el sistema para el doble gasto y detener cualquier intento.

Ferguson (1994, p. 296) argumentó que un observador debe ser producido por una autoridad central, con su propio esquema nativo de firma digital. El problema de este enfoque es la necesidad de incorporar un tercero de confianza y aumentar el costo de las transacciones, lo que hace prohibitivos los micropagos. En tales esquemas, se utilizaron firmas ciegas, incorporando transacciones anónimas que solo serían rastreables en el caso de un intento de doble gasto (Hou & Tan, 2004), minimizando la capacidad de rastrear actividades ilícitas debido a la naturaleza anónima del sistema.

Otros autores señalaron que el anonimato era un componente crítico del comercio electrónico ( Camenisch et al., 1997), y buscaron utilizar un tercero de confianza como fideicomisario, o un conjunto de fideicomisarios, que podrían revocar selectivamente el anonimato de los participantes. Los autores argumentaron que los fideicomisarios solo operarían en casos de sospecha justificada. Sin embargo, la revocación del anonimato ha demostrado ser un problema constante y dicho sistema reduciría el anonimato y la privacidad en general. Es importante destacar que cuando se permite a un gobierno interactuar con la privacidad de las personas en un sistema, es probable que terminen abusando de ese privilegio. De manera crítica, la introducción de un tercero de confianza que actúa como fideicomisario brinda la oportunidad para que los atacantes malintencionados comprometan la privacidad del sistema.

Como observó Ferguson (1994, p. 296), la única protección contra los ataques de doble gasto radica en identificar el ataque o, posteriormente, al usuario que lo realizó. El requisito de un observador se ha basado en la necesidad de contar con algún tipo de autoridad central o tercero de confianza. Hoepman (2006; J.-H. Hoepman , 2010) analizó la implementación de una red distribuida punto a punto en lugar de utilizar una autoridad central. Hird (2002) señaló que se podría implementar un «cambio de costos» inverso para reducir los ataques de spam en el correo electrónico y analizó el problema de generar tokens para establecer una función de precio. Bitcoin integra un ajuste de dificultad para garantizar que el precio se mantenga de manera uniforme.

El proceso en Bitcoin utiliza un algoritmo de prueba de trabajo (Aura et al., 2001). El sistema discutido por Hird (2002) mostró cómo los sistemas distribuidos propuestos por Back (2002) sufrirían el problema demostrado por Hird (2002, pp. 212-213), donde la diferencia en el poder de procesamiento entre los sistemas informáticos permitiría a algunos usuarios para generar tokens más rápido que otros. La diferencia económica entre el poder computacional favorecería a los grandes operadores y facilitadores de botnets sobre los usuarios honestos. En consecuencia, bitcoin fue diseñado como un token económicamente vendible. Al basar la seguridad en un proceso económico en el que las personas están haciendo el trabajo para validar las transacciones, cuando se pagan los tokens, se puede construir un sistema comercial donde los nodos económicamente incentivados compiten para validar soluciones, eliminando el anonimato de dichos sistemas de observadores.

En el proceso, se desarrolla un sistema P2P cooperativo para registrar la primera transacción enviada y alertar a la red de observadores sobre cualquier intento de doble gasto. Ósipkov et al. (2007) crearon un sistema basado en una red cooperativa peer-to-peer diseñada para proporcionar observadores que combatan el doble gasto. El problema con su enfoque fue que los autores, nuevamente, buscaron crear dinero digital anónimo e imposible de rastrear. Uno de los problemas del dinero digital en el pasado había sido el problema del anonimato y la incapacidad de la policía o el sistema de justicia para rastrear a los delincuentes. En consecuencia, se rechazó el uso de firmas ciegas, a pesar de que en el pasado era el enfoque principal para crear sistemas de efectivo electrónico.

Ósipkov et al. (2007) demostraron que un tercero de confianza creó un punto único de falla e introdujo gastos administrativos y de equipo. Alternativamente, la detección en línea del doble gasto, aunque disminuye el tiempo requerido para detectar dicho ataque, aumenta aún más el costo. El enfoque adoptado por los autores fue “exigir que el doble gasto no sea procesable, un requisito natural es hacer que el dinero electrónico sea completamente anónimo e imposible de rastrear” (2007, p. 2). Este enfoque difiere del promovido a través de Bitcoin, que permite la trazabilidad completa de todas las transacciones durante toda la vida del sistema.

El equilibrio buscado en Bitcoin residía en crear un sistema que fuera privado pero no anónimo. El uso de claves desechables, que se pueden generar utilizando las propiedades homomórficas de ECDSA, proporciona un medio para incorporar la identidad y proteger la privacidad. Sin embargo, no elimina la necesidad de desarrollar un sistema que observe el doble gasto e informe sobre tales ataques. La creación de un observador que no mantenga el control sobre el sistema, o la capacidad de desanonimizar a los usuarios eliminando su privacidad, permite un tipo de observador diferente de los implementados en los sistemas de efectivo electrónico anteriores. La dificultad radica en crear un medio para incentivar el comportamiento honesto del observador.

Incentivando a los observadores

La red de Bitcoin implica el intercambio descentralizado de transacciones entre usuarios, donde Alice y Bob pueden negociar directamente mediante transacciones de IP a IP. Además, la red de nodos actúa como un observador incentivado y comercializado . Si bien Ferguson (1994, p. 296) demostró que se podía implementar un sistema de este tipo, existía el requisito de una autoridad central, lo que introducía costos y reducía la resiliencia en todo el sistema. Además, un observador de confianza de este tipo debía ser monitoreado para asegurarse de que no comprometiera la privacidad general de los usuarios del sistema.

Ósipkov et al. (2007, p. 2) promovieron el uso de un sistema cooperativo de igual a igual. Sin embargo, tal metodología no puede proporcionar micropagos tan bajos como una fracción de centavo. El sistema también fue diseñado para proporcionar no rastreabilidad , anonimato y la capacidad de realizar transacciones sin congelar el dinero o alertas en caso de actividad delictiva. Por el contrario, Bitcoin aplica reglas y puede construirse “para aceptar alertas de los nodos de la red cuando detectan un bloque no válido” (Wright, 2008, p. 5). La aplicación de las reglas incluye la ley y, como tal, la capacidad de alertar rápidamente a otros usuarios, no solo sobre monedas «doblemente gastadas», sino también sobre órdenes judiciales o cualquier actividad ilícita, incluido el robo.

La creación de un sistema de sellado de tiempo resuelve parte del problema (Haber & Stornetta , 1991). Sin embargo, la implementación de dichos sistemas mantuvo un enfoque centralizado , lo que condujo a puntos únicos de falla. Además, el sistema de pedidos y sellado de tiempo no tiene una función de pago integrada. El uso de un sistema de pago entre pares no es nuevo con Bitcoin. MojoNation y, posteriormente, Mnet incorporaron un sistema de pago denominado «criptocréditos» (Barr et al., 2001). Yichun ( 2007 ) lanzó un sistema de transacciones peer-to-peer diseñado para detener el doble gasto sin un tercero de confianza.

Palaka et al. (2004) amplió un diseño de protocolo anterior para una criptomoneda anónima peer-to-peer diseñada tanto para «micropagos (menos de 1 euro) como para macropagos» ( Daras et al., 2003, p. 2). Incluso se han desarrollado versiones peer-to-peer de eCash ( Camenisch et al., 2007). Otros autores intentaron crear sistemas basados en incentivos que permitieran la transferencia de valor en sistemas y redes peer-to-peer mientras eliminaban el doble gasto ( Figueiredo et al., 2004). Al igual que con todos los demás sistemas mencionados, los autores buscaron eliminar la trazabilidad e introducir el anonimato en los sistemas de pago.

En muchas formas de pago electrónico que funcionaban en sistemas peer-to-peer, las redes se denominarían observadores (Nambiar & Lu, 2005). La mayoría de los observadores actuaron sin incentivos adecuados (Weber, 1998). La falta de incentivos conduce al parasitismo (Feldman & Chuang, 2005) y al blanqueo (Feldman et al., 2006) en los sistemas peer-to-peer. Si bien los investigadores han promovido metodologías alternativas para rastrear y rastrear a los free riders en redes peer-to-peer ( Karakaya et al., 2008), y señalaron cómo “el problema del free rider representa una seria amenaza para su correcto funcionamiento” ( Karakaya et al. , 2009), ninguno de ellos separó la función de observador del funcionamiento del sistema de pago.

Bitcoin creó un mecanismo de pago descentralizado y permitió a las personas comunicarse directamente de IP a IP sin un intermediario o un tercero de confianza. La necesidad de un observador generalmente hace que los micropagos sean demasiado costosos. En consecuencia, Bitcoin introdujo un sistema de nodos comercial y competitivo. Dichos nodos brindan resiliencia y actúan para formar un consenso sobre qué transacción ocurrió primero. Los nodos validan las transacciones, pero no deciden sino que hacen cumplir las reglas existentes (Wright, 2008, p. 8). De esta forma, los usuarios pueden estar seguros de que la transacción es válida y ser alertados si se produce un intento de doble gasto.

El sistema incentiva la actividad honesta de los nodos al producir un registro de auditoría visible y un registro inmutable de toda la actividad. Si un usuario recibe una transacción gastada dos veces, se puede detectar de inmediato. Los nodos son incentivados mediante el pago de tokens utilizados en el sistema. El despliegue temprano se inició con el subsidio, disminuyendo con el tiempo. A medida que disminuye el subsidio, se espera que los nodos recolecten un mayor número de transacciones y cosechen las tarifas pagadas en cada transacción. Con el tiempo, se espera que el tamaño del bloque en Bitcoin aumente significativamente, hasta el punto en que los nodos se ejecuten en los centros de datos (Wright en Donald, 2008).

La sección 6 (Wright, 2008, p. 4) define el proceso a través del cual se incentivan los nodos . Los nodos apoyan a la red como observadores para su consideración; hecho a través de un pago comercial. La emisión de un contrato unilateral ( Wormser , 1916) se contrapone a una emisión predefinida de un número absoluto de tokens. No hay un tercero o emisor de confianza en curso después de la creación inicial de tokens. Una vez que se ha lanzado el sistema, todos los aspectos del protocolo, incluida la emisión inicial, quedan grabados en piedra y no se permiten cambios en el funcionamiento del sistema.

Como demostró Wormser (1916, p. 136) en un tratado temprano sobre el contrato unilateral, “un contrato unilateral se crea cuando se realiza el acto”. En el caso de un nodo de Bitcoin, el pago se recibe como una combinación de subsidios y tarifas cuando otros nodos verifican, hasta una profundidad de 100 bloques más, el bloque que ha creado un nodo. En este punto se ha producido la creación de un contrato unilateral (Pettit, 1983). Un contrato unilateral se acepta tan pronto como se ha completado la oferta. Un sistema que no crea un bloque, o incluso un sistema que crea un bloque huérfano y por lo tanto no aceptado, no cumple con los términos requeridos por la red para recibir el pago (Smith, 1930).

Un contrato unilateral se puede distinguir de un acuerdo bilateral (Fox, 1939). La oferta a los usuarios del sistema difiere de la oferta a los nodos. Se incentiva a los nodos para que soporten la red. La metodología utilizada para distribuir las monedas también incentivó la inversión en la red. Sin una autoridad central capaz de continuar acuñando o emitiendo nuevas monedas, Bitcoin tiene un suministro fijo que debe aumentarse utilizando volúmenes crecientes de tarifas. Como señala el libro blanco, “el incentivo también se puede financiar con tarifas de transacción” (Wright, 2008, p. 4). Este se convierte en el método principal para que los nodos obtengan ingresos. A través de dicho proceso, se incentiva a los nodos para que actúen como «observadores».

En la sección 6 del informe técnico, también podemos ver que los nodos y los usuarios son entidades separadas. Como se define en el documento, el incentivo para que los nodos admitan la red lo proporciona la transacción coinbase que inicia una nueva moneda. La moneda es propiedad del creador del bloque (Wright, 2008, p. 4). El creador de un bloque se define como un nodo que encuentra una solución hash válida, validando un bloque construido sobre otros nodos, hasta una profundidad de 100 bloques. Eventualmente, el único modelo de ingresos proporcionado a los nodos radica en el cobro de tarifas.

Los nodos también serán usuarios del sistema Bitcoin y utilizarán los tokens. Como un nodo se paga con tokens de Bitcoin, será necesario que el operador del nodo intercambie los tokens por otras formas de dinero (Feldman & Chuang, 2005). Al hacerlo, será necesario para pagar facturas e impuestos y para mantener el negocio operado por el nodo. Como tal, el nodo es tanto un usuario del sistema como un operador del sistema. Los incentivos proporcionados en este modelo económico mantienen la seguridad de Bitcoin. Se han desarrollado otros sistemas para monitorear redes peer-to-peer, proporcionar efectivo digital y evitar el doble gasto utilizando una combinación de observadores y sistemas de intercambio.

La distinción en Bitcoin radica en la implementación de un sistema de efectivo digital basado en la privacidad, no en el anonimato, y un requisito para que el sistema mantenga la trazabilidad. Los intentos previos de un sistema peer-to-peer han requerido observadores sin incentivos económicos , que actuaron de manera altruista. Tal modelo no es sostenible (Feldman & Chuang, 2005). Sin embargo, aunque la gente ha afirmado que Bitcoin es el primer sistema de efectivo digital distribuido o de igual a igual, es un error ( Figueiredo et al., 2004). Más bien, Bitcoin es el primer sistema económicamente incentivado que distribuye pagos a través de un sistema automatizado unilateral basado en contratos que no requiere un operador central.

La razón por la que Bitcoin no requiere un operador central es que la emisión de tokens se completó en el lanzamiento del producto y la distribución está automatizada. Los requisitos para mantener el sistema están definidos y grabados en piedra. En otras palabras, el protocolo no cambia. Como el protocolo no cambia, y el sistema de incentivos está definido para operar sin interacción, el sistema se convierte en el primer sistema desarrollado para continuar operando sin la interacción continua de un tercero. Es solo porque el sistema no cambia y el protocolo es fijo que es posible. Si se pudiera cambiar Bitcoin, o cualquier sistema análogo, y el protocolo no se arreglara, las partes, como los desarrolladores, tendrían derecho a alterar el sistema y, por lo tanto, mantener el poder sobre él. Tales entidades se convertirían en fiduciarios y terceros de confianza.

Conceptos alternativos que explican ‘Peer-to-Peer’

Otros investigadores promovieron el concepto de resistencia a la censura (Waldman & Mazières , 2001). Sin embargo, el reclamo solo se asoció con Bitcoin en 2011 y nunca formó parte del sistema original ( Barok , 2011; Reitman, 2011). Junto con hacer el reclamo y el deseo de hacer que Bitcoin sea resistente a la censura, muchos desarrolladores de BTC Core comenzarían a trabajar para modificar el protocolo (Todd, 2013) y limitar los aumentos en el tamaño del bloque. El deseo era crear un sistema que Endsuleit et al. (2006), Ngan et al. (2003) y Goldberg (2007) promocionaron como necesarias para detener la usurpación del gobierno. Sin embargo, lo que cada uno de ellos ignoró es el requisito principal de los sistemas democráticos para que los ciudadanos se comprometan y sean políticamente activos.

Bitcoin no es resistente a la censura en la forma en que a menudo se promueve, o en la forma en que otros investigadores, incluidos Dingledine y Mathewson (2006), Roussopoulos et al. (2005), o Wallach et al. (2003), propugnada. Bitcoin incluía explícitamente la capacidad de eliminar transacciones de un bloque (Wright, 2008, p. 4). El argumento de que es posible que nunca se eliminen las transacciones no se basa en la tecnología original. Más bien, el modelo de Bitcoin consiste en registrar todas las transacciones y registrar todos los datos. La información se puede modificar o eliminar de la cadena de bloques de Bitcoin. Pero, tal acción deja un registro y constancia del cambio. Por ejemplo, si se elimina una transacción después de una orden judicial, la orden judicial en sí formaría un aspecto permanente de la cadena de bloques, y los investigadores podrían monitorear y analizar cuántas órdenes judiciales se han emitido.

Aquellos que dicen que Bitcoin es el primer sistema distribuido peer-to-peer para dinero electrónico no han hecho su tarea o simplemente son completamente engañosos. La respuesta simple es que es muy fácil determinar que los sistemas de efectivo digital peer-to-peer existían mucho antes de la llegada de Bitcoin. Como se explicó, Osipkov et al. (2007), por ejemplo, describió cómo la introducción de observadores puede ayudar a tomar medidas contra el doble gasto. Dichos observadores son nodos peer-to-peer.

Otros investigadores han utilizado el término ‘pagos entre pares’, análogo a Bitcoin ( Havinga et al., 1996). Aquí se hace referencia a los pagos entre pares en el contexto de brindar transferibilidad entre usuarios individuales. Dicho sistema reflejaría la funcionalidad de IP a IP incluida en el protocolo Bitcoin original. Sin embargo, Havea (1996, p. 3) también hace referencia al efectivo como un sistema anónimo y no como uno que es meramente privado. Si bien Bitcoin utilizó un sistema de creación de nuevas claves para que un «banco o cualquier otra parte no pueda determinar si el mismo usuario realizó dos pagos» ( Havinga et al., 1996, p. 3), otros autores han hizo la presunción de que la trazabilidad no debería ser una función del dinero.

Bitcoin se diferencia por ser un sistema privado que mantiene una capacidad completa para rastrear transacciones de principio a fin. La capacidad de Bitcoin para mantener la inmutabilidad radica en su función de registro y no en la llamada funcionalidad de «resistencia a la censura» que algunas personas promueven ( Barok , 2011). El “deseo de los reguladores e intermediarios de poder rastrear cualquier transacción en la economía”, que han señalado los investigadores contemporáneos de criptomonedas y dinero digital ( Havinga et al., 1996, p. 3), es una preocupación válida. Se debe mantener el equilibrio entre la privacidad y la capacidad de rastrear el dinero y proteger al público de la delincuencia.

Bitcoin equilibra esa dicotomía al lograr privacidad a través de la escala. Si bien cada transacción conserva la trazabilidad total, el costo de monitorear a todos los usuarios a nivel mundial es prohibitivo. Además, suponga que los usuarios mantienen claves separadas para cada transacción y bloquean sus identidades. En ese caso, se vuelve inviable que las personas determinen aleatoriamente las identidades de otras personas o incluso que vinculen identidades. La creación de filtros, controles y software puede simplificar el problema y permitir pagos que no sean conjuntos y, por lo tanto, no expongan la identidad del usuario ni vinculen transacciones (Wright, 2008).

Introducción a la resiliencia

Un tercero de confianza o una autoridad central crea un único punto de falla. La descentralización de Bitcoin se logra a través de la interacción de individuos a través de la red, que se facilita principalmente a través de comunicaciones directas de IP a IP. La capacidad de partes como Alice y Bob para comunicarse directamente, sin pasar por un nodo, es esencial para que el sistema mantenga la descentralización . Además, una red de observadores entre pares es más resistente que una parte central de confianza. Tal resiliencia significa que es más difícil atacar la red Bitcoin ( Palaka et al., 2004). La capacidad de resistir ataques y brindar servicios justos constituye uno de los aspectos centrales de Bitcoin.

Los nodos no establecen las reglas dentro del protocolo Bitcoin. Se arreglaron cuando se lanzó el protocolo. Más bien, los nodos hacen cumplir las reglas. La capacidad de alertar a la red y actuar dentro de un marco legal es un requisito clave para cualquier sistema, incluido Bitcoin. Otras entidades han considerado el seguimiento de monedas como un sistema que puede llevarse a cabo a través de terceros de confianza (Hou & Tan, 2004) o un protocolo de autodesanonimización. Ninguna opción es adecuada. En cambio, Bitcoin crea un conjunto de nodos comerciales independientes que actúan como observadores de la red. La resiliencia del sistema se logra a través de un conjunto distribuido de operadores competidores.

Cada nodo actúa de forma independiente en una red de sellado de tiempo entre pares (Voulgaris et al., 2005). En dicho proceso, los nodos que fallan o son atacados con éxito hacen que sea económicamente más viable que se unan otros nodos. Las tarifas se distribuirán entre una pequeña cantidad de nodos si uno desaparece. En consecuencia, la rentabilidad de todos los nodos restantes aumenta significativamente. El proceso incentiva a nuevos nodos a unirse, llenando el vacío dejado por el nodo saliente. La estructura de incentivos continuos asegura que la red de observadores entre pares se mantenga y opere abiertamente, con auditabilidad.

Conclusión

Bitcoin resolvió el problema del doble gasto de manera sólida y segura. Lo hizo mediante la formación de una red de observadores entre pares que tiene incentivos económicos . Si bien han existido otras redes para proporcionar capacidades de observación (Hou & Tan, 2004), y el efectivo digital entre pares se propuso varias veces ( Daras et al., 2003; Figueiredo et al., 2004; Palaka et al., 2004). ), todos buscaban formar un sistema de efectivo electrónico que fuera imposible de rastrear y anónimo. Bitcoin no es el primer sistema de efectivo digital peer-to-peer. Asimismo, Bitcoin no es el primer sistema de efectivo digital descentralizado . Bitcoin es el primer sistema que utiliza una red peer-to-peer creada con incentivos económicos y, lo que es más importante, que mantiene una trazabilidad completa, utilizando la privacidad en lugar del anonimato.

Solving Double-Spending

Incentivising Observers

Alternative Concepts Explaining ‘Peer-To-Peer’

Introducing Resilience

Conclusion

Aura, T., Nikander, P., & Leiwo, J. (2001). DOS-Resistant Authentication with Client Puzzles. In B. Christianson, J. A. Malcolm, B. Crispo, & M. Roe (Eds.), Security Protocols (pp. 170–177). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-44810-1_22

Back, A. (2002). Hashcash-amortizable publicly auditable cost functions. Available HTTP: Http://Www. Hashcash. Org/Papers/Amortizable. Pdf.

Barok, D. (2011). Bitcoin: Censorship-resistant currency and domain name system to the people. Piet Zwart Inst.

Barr, K., Batten, C., Saraf, A., & Trepetin, S. (2001). pStore: A Secure Distributed Backup System. Technischer Bericht, LCS, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Brands, S. (1994). Untraceable Off-line Cash in Wallet with Observers. In D. R. Stinson (Ed.), Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’ 93 (pp. 302–318). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-48329-2_26

Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A., & Meyerovich, M. (2007). Endorsed E-Cash. 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP ’07), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1109/SP.2007.15

Camenisch, J., Maurer, U., & Stadler, M. (1997). Digital payment systems with passive anonymity-revoking trustees. Journal of Computer Security, 5(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.3233/JCS-1997-5104

Daras, P., Palaka, D., Giagourta, V., & Bechtsis, D. (2003). A novel peer-to-peer payment protocol. The IEEE Region 8 EUROCON 2003. Computer as a Tool., 1, 2–6 vol.1. https://doi.org/10.1109/EURCON.2003.1247967

Dingledine, R., & Mathewson, N. (2006). Design of a blocking-resistant anonymity system. Technical report, The Tor Project. https://r.jordan.im/download/technology/Design%20of%20a%20blocking-resistant%20anonymity%20system.pdf

Donald, J. A. (2008, November 3). Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper [Metzdowd.com.]. Bitcoin P2P E-Cash Paper. https://www.metzdowd.com/pipermail/cryptography/2008-November/014819.html

Endsuleit, R., & Mie, T. (2006). Censorship-resistant and anonymous P2P filesharing. First International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES’06), 7–65. https://doi.org/10.1109/ARES.2006.41

Feldman, M., & Chuang, J. (2005). Overcoming free-riding behavior in peer-to-peer systems. ACM SIGecom Exchanges, 5(4), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1145/1120717.1120723

Feldman, M., Papadimitriou, C., Chuang, J., & Stoica, I. (2006). Free-riding and whitewashing in peer-to-peer systems. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, 24(5), 1010–1019. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2006.872882

Ferguson, N. (1994). Extensions of Single-term Coins. In D. R. Stinson (Ed.), Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’ 93 (pp. 292–301). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-48329-2_25

Figueiredo, D. R., Shapiro, J. K., & Towsley, D. (2004). Payment-based incentives for anonymous peer-to-peer systems. Computer Science Department, University of Massachusetts. ftp://128.119.245.9/pub/Anon_Incentive_04-62.pdf

Fox, J. H. Jr. (1939). Contracts—Offer of Unilateral Contract Distinguished from Unilateral and Bilateral Contract—Effect of Beginning Acceptance of Offer of Unilateral Contract Recent Decision. Mississippi Law Journal, 12(3), 374–377.

Goldberg, I. (2007). Privacy-Enhancing Technologies for the Internet III: Ten Years Later. In Digital Privacy (pp. 25–40). Auerbach Publications. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420052183-7

Haber, S., & Stornetta, W. S. (1991). How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document. In A. J. Menezes & S. A. Vanstone (Eds.), Advances in Cryptology-CRYPTO’ 90 (pp. 437–455). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-38424-3_32

Havinga, P. J. M., Smit, G. J. M., & Helme, A. (1996). SURVEY OF ELECTRONIC PAYMENT METHODS AND SYSTEMS. 8.

Hird, S. (2002). Technical solutions for controlling spam. Proceedings of AUUG2002. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=CPXLz_zkhgwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA205&dq=Technical+Solutions+for+Controlling+Spam.+&ots=rN9Q3Uaoqm&sig=WOsugqcrnrRbPeiBJ_goUjkwrr0#v=onepage&q=Technical%20Solutions%20for%20Controlling%20Spam.&f=false

Hoepman, J. (2006). Distributed Double Spending Prevention. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.183.6025

Hoepman, J.-H. (2010). Distributed Double Spending Prevention. In B. Christianson, B. Crispo, J. A. Malcolm, & M. Roe (Eds.), Security Protocols (pp. 152–165). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17773-6_19

Hou, X., & Tan, C. H. (2004). Fair traceable off-line electronic cash in wallets with observers. The 6th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology, 2004., 2, 595–599. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACT.2004.1292939

Karakaya, M., Körpeoğlu, İ., & Ulusoy, Ö. (2008). Counteracting free riding in Peer-to-Peer networks. Computer Networks, 52(3), 675–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2007.11.002

Karakaya, M., Korpeoglu, I., & Ulusoy, Ö. (2009). Free Riding in Peer-to-Peer Networks. IEEE Internet Computing, 13(2), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2009.33

Lee, H. J., Choi, M. S., & Rhee, C. S. (2003). Traceability of double spending in secure electronic cash system. 2003 International Conference on Computer Networks and Mobile Computing, 2003. ICCNMC 2003., 330–333. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCNMC.2003.1243063

Nambiar, S., & Lu, C.-T. (2005). M-Payment Solutions and M-Commerce Fraud Management [Chapter]. Advances in Security and Payment Methods for Mobile Commerce; IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-345-6.ch009

Ngan, T.-W. “Johnny”, Wallach, D. S., & Druschel, P. (2003). Enforcing Fair Sharing of Peer-to-Peer Resources. In M. F. Kaashoek & I. Stoica (Eds.), Peer-to-Peer Systems II (pp. 149–159). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-45172-3_14

Osipkov, I., Vasserman, E. Y., Hopper, N., & Kim, Y. (2007). Combating Double-Spending Using Cooperative P2P Systems. 27th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS ’07), 41–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDCS.2007.91

Palaka, D., Daras, P., Petridis, K., & Strintzis, M. (2004). A Novel Peer-to-Peer Payment System. (p. 250).

Pettit, M. Jr. (1983). Modern Unilateral Contracts. Boston University Law Review, 63(3), 551–596.

Reitman, R. (2011). Bitcoin—A Step Toward Censorship-Resistant Digital Currency. In Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2011/01/bitcoin-step-toward-censorship-resistant

Roussopoulos, M., Baker, M., Rosenthal, D. S. H., Giuli, T. J., Maniatis, P., & Mogul, J. (2005). 2 P2P or Not 2 P2P? In G. M. Voelker & S. Shenker (Eds.), Peer-to-Peer Systems III (pp. 33–43). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-30183-7_4

Smith, W. A. (1930). Acceptance of Offer for Unilateral Contract—Necessity of Notice to Offeror Editorial Notes. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 4(1), 57–85.

Todd, P. (2013, March 7). [Bitcoin-development] Large-blocks and censorship. https://lists.linuxfoundation.org/pipermail/bitcoin-dev/2013-March/002199.html

Voulgaris, S., Jelasity, M., & van Steen, M. (2005). A Robust and Scalable Peer-to-Peer Gossiping Protocol. In G. Moro, C. Sartori, & M. P. Singh (Eds.), Agents and Peer-to-Peer Computing (pp. 47–58). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-25840-7_6

Waldman, M., & Mazières, D. (2001). Tangler: A censorship-resistant publishing system based on document entanglements. Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1145/501983.502002

Wallach, D. S. (2003). A Survey of Peer-to-Peer Security Issues. In M. Okada, B. C. Pierce, A. Scedrov, H. Tokuda, & A. Yonezawa (Eds.), Software Security—Theories and Systems (pp. 42–57). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-36532-X_4

Weber, R. (1998). Chablis—Market Analysis of Digital Payment Systems. https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/1094458

Wormser, I. M. (1916). True Conception of Unilateral Contracts. Yale Law Journal, 26(2), 136–142.

Wright, C. S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3440802

Wright, C. S., & Savanah, S. (2022). Determining a common secret for the secure exchange of information and hierarchical, deterministic cryptographic keys (United States Patent No. US11349645B2). https://patents.google.com/patent/US11349645B2/en?assignee=nchain&before=priority:20160301

Yi-chun, L. (2007). An Optimistic Fair Peer-to-Peer Payment System. 2007 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering, 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMSE.2007.4421852

Dejar un comentario

¿Quieres unirte a la conversación?Siéntete libre de contribuir!