Firmas digitales … Por Craig S Wright

Científico jefe de nChain e inventor de Bitcoin y más de 1000 cosas.

Publicada el 6 de julio de 2022

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/firmas-digitales-craig-s-wright/

Las firmas digitales proporcionan parte de la solución, pero los principales beneficios se pierden si aún se requiere un tercero de confianza para evitar el doble gasto…

El Libro Blanco de Bitcoin señala el uso de un algoritmo de firma digital y su necesidad de evitar el despliegue de terceros de confianza o sistemas alternativos. Sin embargo, en el núcleo, Core de BTC se han desarrollado sistemas alternativos, como The Lightning Network (Antonopoulos et al., 2021) y con SegWit (Pérez-Solà et al., 2019), se ha reintroducido el requisito de un tercero (Faltibà, 2018, p. 16).

Como señala la oración, las firmas digitales proporcionan parte de la solución. Este aspecto de bitcoin en sí mismo no es nuevo. Wayner (1996) documentó múltiples requisitos para firmas digitales (Wayner, 1996, p. 28) y algoritmos de firma digital (Wayner, 1996, p. 18) y múltiples formas de efectivo digital o electrónico más de una década antes del lanzamiento de Bitcoin. Una solución de esta época incluye sistemas de clave pública de solo firma (Wayner, 1996, p. 17).

El uso de sistemas de clave pública de solo firma, se define en el trabajo de Wayner (1996, p. 17), señalando que un sistema que se puede usar para verificar una firma, pero que no se usa para cifrar mensajes y, por lo tanto, «mantenerlos fuera». de los ojos y oídos de la policía” se puede crear de una manera que no “tiende(n) a molestar a algunos gobiernos que quieren controlar el uso de la encriptación”. Dichos sistemas difieren de las firmas digitales ciegas, que se utilizan, para crear efectivo anónimo (Wayner, 1996, p. 18). Los usuarios de Bitcoin tienen un sistema de firma, no ciego, que no está encriptado. Los sistemas de firma mentalizados han existido desde la década de 1980.

Como señala la segunda oración del documento técnico, las firmas digitales proporcionan parte de la solución. Se requieren muchos otros aspectos de bitcoin, para que sea seguro y funcione. Sin embargo, algunos de los beneficios siguen siendo mal entendidos. Principalmente, Bitcoin es un sistema de micro pagos. El sistema tiene como objetivo proporcionar la capacidad de efectivo electrónico que se puede distribuir como «pequeñas transacciones casuales» (Wright, 2008, p. 1). Sin embargo, para las transacciones de gran valor, las normas sobre blanqueo de capitales y transacciones financieras exigen el uso de intermediarios (Geiger & Wuensch, 2007).

Bryans (2014) señaló cómo bitcoin requiere disposiciones contra el lavado de dinero y que la aplicación de AML requiere que las transacciones de gran valor (generalmente más de USD 10,000) requieran informes e intermediarios. Estos requisitos también son necesarios para los pagos en efectivo. Entonces, la introducción de Bitcoin no mitiga este requisito. Dado que el dinero en efectivo en su forma física puede usarse, para el lavado de dinero, el argumento de que Bitcoin es diferente, porque es similar al dinero en efectivo no tiene sentido. Más bien, Bitcoin es similar al efectivo y, por lo tanto, requiere el uso de las mismas reglas existentes que se aplican a las transacciones en efectivo. La distinción es que Bitcoin es completamente rastreable, y cualquier transacción que se realice por valores grandes se puede monitorear e informar fácilmente según el Libro Blanco original, «cualquier regla e incentivo necesarios se pueden hacer cumplir con este mecanismo de consenso» (Wright, 2008, pág. 8).

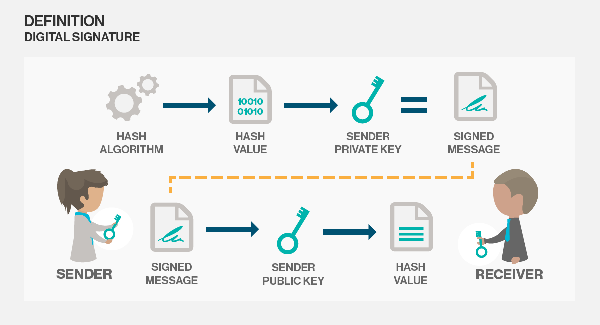

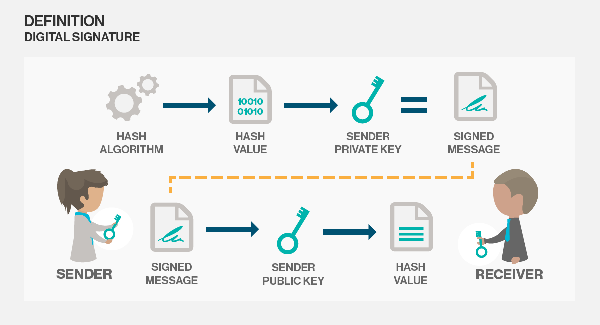

¿Que es una firma digital?

Las diversas definiciones y requisitos relacionados con las firmas e identidades electrónicas están documentados en detalle por Brazell (2018). (2014) En este trabajo sobre firmas e identidades electrónicas, el autor documenta los estándares, los requisitos técnicos, los problemas de identidad y los desafíos jurisdiccionales asociados con las firmas digitales. Estas definiciones se proporcionan en un contexto global. En el “nuevo modelo de privacidad” (Wright, 2008, p. 6) proporcionado por Bitcoin, las identidades siguen siendo una parte necesaria de la solución. La distinción es que el público puede ver a alguien enviando información, pero no puede relacionarla con nadie.

Este modelo de privacidad, no elimina la necesidad de identidad (Bryans, 2014). Más bien, el nuevo modelo de privacidad producido por un Bitcoin permite a las personas intercambiar identidades cuando sea necesario y al nivel que sea necesario. Por ejemplo, dos personas que se dedican a un comercio pequeño, como comprar un café, no necesitan intercambiar grandes cantidades de información. En cambio, la cafetería puede proporcionar información sobre la identidad comercial en forma de factura, y el usuario puede ser tratado como una persona que paga en efectivo. De esta manera, el nivel de transacción dicta cuánta información debe intercambiarse y ninguna de esta información debe conectarse a la cadena.

Las firmas siempre pueden ser repudiadas (Brazell, 2018, p. 298). El repudio o no repudio, no es una cuestión técnica, y los intentos de crear no repudio a través de metodologías técnicas no lograron comprender los requisitos legales (Brazell, 2018, p. 90). Como señala Brazell (2018, pp. 90–91) en la sección 4-054;

- Se cree ampliamente que una firma digital reduce la libertad del firmante para repudiar una firma electrónica por cualquier motivo que no sean los igualmente disponibles con respecto a las firmas manuscritas, a saber, error, coacción y similares. Sin embargo, este no es el caso debido a la incapacidad de la firma digital para identificar al firmante. Una firma digital solo proporciona para qué se usó una clave para firmar, no las circunstancias en las que se usó. Esta brecha entre la firma y el signatario conduce a la necesidad de una asignación legal de responsabilidad por las consecuencias de la firma, que se aborda en la Ley Modelo de la CNUDMI sobre firmas electrónicas. Un biométrico, por otro lado, puede proporcionar una genuina falta de reputación.

- Sin embargo, como muestra esta revisión, las firmas digitales no tienen ninguna ventaja particular sobre otras formas de firma electrónica con respecto a muchas de las funciones para las cuales se utiliza una firma manuscrita y, en particular, tienen fallas significativas cuando se trata de la función de identificar al firmante. con confianza. Para producir una firma electrónica que pueda realizar todas las funciones de una firma manuscrita, se requiere una combinación de tecnología biométrica y de firma digital.

Bitcoin puede funcionar como dinero en efectivo, pequeños valores indiscutibles donde el costo de buscar repudiar la transacción excede el valor de la cantidad intercambiada en comparación con la cantidad necesaria para ir a los tribunales y objetar el intercambio. En esto, las transacciones dentro de bitcoin. En montos inferiores a $10,000, habrá pocas posibilidades de recuperar fondos de manera significativa. Incluso en la corte de reclamos menores, el costo de recuperación excederá cualquier beneficio obtenido al buscar una orden judicial para recuperar el dinero distribuido a través de bitcoin. Por el contrario, para grandes cantidades, es posible crear una estrategia, que alerte a los nodos para rechazar bloques que han sido congelados por orden judicial.

“Una de esas estrategias para protegerse contra esto sería aceptar alertas de los nodos de la red cuando detectan un bloque no válido, incitando al software del usuario a descargar el bloque completo y alertando a las transacciones para confirmar la inconsistencia” (Wright, 2008, p. 5). Por ejemplo, crear un bloque que implemente y permita una transacción desde un UTXO congelado se consideraría inválido. Este proceso se puede automatizar, lo que permite que los nodos tomen medidas fácilmente contra los fondos delictivos o el dinero que ha sido incautado a través de una orden judicial.

Dicho proceso se completaría en dos partes con el congelamiento y luego la reasignación de fondos. Sin embargo, como se señaló anteriormente (Brazell, 2018), el no repudio, no es algo que sea posible en todos los sistemas electrónicos y sigue siendo algo que legalmente se requiere que sea reversible a través de procesos judiciales. Es importante destacar que el Libro Blanco de Bitcoin no señala que el sistema protege la posesión, sino que protege la «propiedad».

Los principales beneficios que se discuten en el documento técnico de Bitcoin están relacionados con el uso del sistema en efectivo electrónico. Sin embargo, cuando hay terceros, el sistema requiere un medio de gestión de accesos y usos que es más costoso que el que se puede entregar en Bitcoin. En esto, en lugar de tener un sistema de efectivo electrónico, “pequeños pagos casuales”, terminamos con un sistema de oro digital, que es costoso y menos efectivo que los bancos y la infraestructura financiera existente. El Santo Grial de Internet siempre fue el dinero digital (Wayner, 1996). La diferencia con Bitcoin es que, en lugar de crear un sistema anónimo imposible de rastrear como eCash (Chaum, 1983), Bitcoin creó un sistema privado o seudónimo que mantiene el fin y la rastreabilidad.

La distinción entre estas ideas está en la creación de una Criptomoneda como en eCash contra efectivo digital, o un sistema de efectivo electrónico se ejemplifica en Bitcoin. Bitcoin es privado y seudónimo. Sin embargo, esto no mitiga la necesidad de identidad. Brazell (2018, pp. 37–62) documenta los requisitos de identidad y su referencia a las firmas digitales. El aspecto clave de Bitcoin que muchas personas olvidan o no entienden es que, una firma digital requiere una identidad.

La Ley Modelo de la CNUDMI sobre Firmas Electrónicas (2001) fue la base de gran parte de la legislación sobre firmas digitales promulgada en todo el mundo, incluida la de EE. UU. y el Reino Unido. Las disposiciones europeas también siguen la Ley modelo. En cada caso, es importante señalar que una función clave de una firma incluye “identificar al autor o remitente de un documento” (Brazell, 2018, p. 15). Por lo tanto, el uso de firmas digitales no se conoce simplemente como el uso de un algoritmo de firma digital. Un algoritmo de firma digital es un sistema tecnológico que brinda la capacidad de crear una firma digital, pero no es en sí mismo una firma digital.

Para ser una firma digital todavía se requiere una identidad. Para transacciones de alto nivel y valor, la identidad se puede proporcionar a través de autoridades de certificación y PKI (Hunt, 2001). Sin embargo, para transacciones de bajo valor, es posible crear una red de confianza (Caronni, 2000) donde no se requiere información detallada sobre las personas o se intercambian identidades parciales (Brazell, 2018, pp. 39–40). El uso de identidades completas o parciales se basará en el tamaño de la transacción y la necesidad del intercambio de información de identidad para el escenario particular.

Como observó Caronni (2000), una red de confianza permite que un usuario del sistema elija por sí mismo a quién considera confiable. En el intercambio de transacciones casuales de pequeño valor, la capacidad de crear un intercambio irreversible es importante. Si una persona compra un artículo de poco valor, aún puede solicitar un reembolso y negociarlo en efectivo. Las interacciones derivadas de las personas que utilizan efectivo electrónico no cambian significativamente con respecto al efectivo físico.

En esta frase del Libro Blanco, el requisito es crear un sistema de firma digital. En esto, las claves pueden derivarse utilizando las propiedades homomórficas de ECDSA que permiten crear una subclave (Wright & Savanah, 2022). Dicho sistema mantiene la identidad, pero también hace que la transmisión de claves a través de la red Blockchain sea públicamente rastreable, mientras que no está directamente vinculada públicamente a la identidad del individuo. Como tal, la trazabilidad permanece, pero las transacciones casuales igualmente pequeñas pueden ocultarse del mundo.

Los beneficios definidos en el Libro Blanco de Bitcoin están relacionados con la capacidad de minimizar el tamaño de la transacción. Eso es efectivo electrónico y micro pagos. Bitcoin se ha promocionado falsamente como oro digital (Popper, 2015); sin embargo, la realidad es que el sistema no tiene tales propiedades. Bitcoin escala y tiene valor como sistema de pago que resuelve los problemas clave con el dinero digital y el comercio electrónico (Wayner, 1996) que se han discutido durante décadas. Sin embargo, Bitcoin puede ser costoso a menos que el volumen de transacciones se mantenga a un ritmo alto. La compensación es el número de nodos versus el tipo de sistema.

Sin embargo, el Libro Blanco de Bitcoin no menciona la descentralización. El documento señala en la sección 2 (Wright, 2008, p. 2) que “[una] solución común es introducir una autoridad central de confianza, o casa de moneda, que verifique cada transacción en busca de doble gasto”. Bitcoin eliminó la necesidad de una autoridad emisora central al automatizar el proceso. Todos los tokens de bitcoin se emitieron en enero de 2009. La emisión única se combinó con un proceso de distribución automatizado en este proceso. Esto eliminó la necesidad de tener una sola autoridad central o casa de moneda de confianza. Más bien, una pluralidad de organizaciones competidoras se auditan y verifican entre sí.

Además de esto, cualquier usuario del sistema puede ver y auditar transacciones (Monrat et al., 2019). Más importante aún, al enviar transacciones entre sí, individuos como Alice y Bob pueden validar individualmente sus propias transacciones y mantener evidencia de cualquier alteración o cambio. Este aspecto es una parte importante de Bitcoin. Las funciones SPV (Simple Payment Verification) de Bitcoin, permiten a las personas verificar y mantener la cantidad de tokens que poseen, validarlos y asegurarse de que nada haya sido alterado.

Cuando Alice quiere transmitir información a Bob, puede verificar su propio conjunto de tokens y asegurarse de que sean válidos sin cambios. Bob puede hacer lo mismo cuando Alice le entrega la transacción. La capacidad de rastrear transacciones en Blockchain le permite a Bob validar la transacción de entrada de Alice sin mantener una copia completa de la Blockchain de Bitcoin. Las funciones SPV de Bitcoin le permiten validar la transacción de Alice usando la ruta de Merkle (Merkle tree) y los encabezados de bloque con hash. Si algo cambia en los encabezados hash del bloque, todos los usuarios del sistema recibirán una alerta y sabrán que algo ha sido alterado. Pueden hacer esto sin mantener una copia completa de Blockchain.

Cuando el Libro Blanco establece que las firmas digitales proporcionan parte de la solución, se refiere a la primera oración, que detalla una versión puramente de igual a igual del efectivo electrónico. Eso fue explicado en el artículo anterior. Como señala la primera oración, el requisito es que los pagos se envíen directamente de una parte a otra, sin pasar por una institución financiera. Como se trata de una versión de efectivo electrónico “puramente entre pares” (Schollmeier, 2001), el requisito es la comunicación directa entre las partes y no la comunicación a través de nodos.

Para que esto funcione, la solución debe funcionar haciendo que Alice envíe comunicaciones directamente a Bob a través de las metodologías de intercambio de IP a IP integradas en Bitcoin y en los primeros días. Si bien BTC y otros sistemas han eliminado los intercambios de IP a IP, esto también elimina el aspecto descentralizado de Bitcoin. Bitcoin no está descentralizado debido a los nodos. Bitcoin está descentralizado porque las personas pueden comunicarse directamente sin usar nodos para el intercambio. En esta serie de comunicaciones, Alice y Bob pueden intercambiar y negociar extensamente, enviando solo la transacción final en la cadena.

En este proceso, pueden crear facturas y órdenes de compra y guardar hashes de estos documentos, que demuestran el intercambio de información entre las dos partes, sin que esta información entre en cadena (Blockchain). Alice y Bob pueden demostrar su identidad entre sí mientras mantienen toda esta información fuera de la cadena y se aseguran de seguir el «nuevo modelo de privacidad» defendido dentro de Bitcoin (Wright, 2008, p. 6).

Bitcoin ofrece una solución para el suministro de efectivo electrónico y pagos de una parte a otra, sin utilizar una institución financiera. El efectivo electrónico no es un sistema que deba diseñarse, para transferir millones de dólares sin ninguna evidencia de respaldo. Así como el efectivo requiere que se intercambie información adicional y que se lleve a cabo el aprovisionamiento AML, el efectivo electrónico sigue las mismas regulaciones. Bitcoin simplifica este proceso al automatizar muchos de los intercambios. Esto no hace un sistema anónimo; hace un sistema privado o seudónimo, con la información relativa al intercambio que no sea pública. Sin embargo, el hecho de que la información no sea pública, no significa que no exista.

Conclusión

Las firmas digitales requieren un algoritmo de firma digital como ECDSA y la capacidad de intercambiar identidades. El intercambio de información basada en la identidad se puede realizar en Bitcoin utilizando las propiedades homomórficas de ECDSA, para que las claves se puedan vincular de forma demostrable a una clave de identidad, sin dejar de ser privadas (Wright & Savanah, 2022). Como señala el sistema, los sistemas tradicionales de efectivo electrónico basados en firmas digitales han requerido el uso de un tercero de confianza o, como se denomina alternativamente, un intermediario de pago. Bitcoin elimina este requisito al tener un sistema competitivo distribuido de nodos, que actúan como un servidor de marcas de tiempo.

Estos nodos no son la metodología principal para difundir y distribuir transacciones. Más bien, los nodos marcan la hora y un índice de los intercambios realizados directamente entre Bob y Alice. En lugar de tener un tercero de confianza, Bitcoin utiliza un sistema competitivo donde las entidades corporativas que ejecutan nodos, intentan encontrar soluciones a los problemas más rápido que su competencia y ganan más dinero. Juntas, las firmas digitales permiten que Bob y Alice intercambien valor de forma segura, mientras que la red de nodos indexa las transacciones mediante un proceso automatizado, que garantiza que las transacciones gastadas dos veces se alerten rápidamente en toda la red.

Referencias

Antonopoulos, AM, Osuntokun, O. y Pickhardt, R. (2021). Dominar la red Lightning: un protocolo blockchain de segunda capa para pagos instantáneos de bitcoin. O´Reilly.

Brazell, L. (2018). Firmas e Identidades Electrónicas: Ley y Reglamento. Dulce y Maxwell.

Bryans, D. (2014). Bitcoin y el lavado de dinero: Minería para una solución efectiva Nota. Revista de derecho de Indiana, 89 (1), 441–472.

Caronni, G. (2000). Recorriendo la Web de la confianza. Actas IEEE 9th International Workshops on Habilitando Tecnologías: Infraestructura para Empresas Colaborativas (WET ICE 2000), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1109/ENABL.2000.883720

Chaum, D. (1983). Firmas ciegas para pagos imposibles de rastrear. Avances en criptología, 199–203.

Faltibá, Z. (2018). The Lightning Network—Sorprendente claridad sobre la economía del tercer milenio. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.25320.01283

Geiger, H. y Wuensch, O. (2007). La lucha contra el lavado de dinero: un análisis económico de una paradoja costo ‐ beneficio. Diario de control de lavado de dinero, 10 (1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/13685200710721881

Caza, R. (2001). PKI e infraestructura de certificación digital. Actas. Novena Conferencia Internacional IEEE sobre Redes, ICON 2001. , 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICON.2001.962346

Monrat, AA, Schelén, O. y Andersson, K. (2019). Una encuesta de Blockchain desde la perspectiva de las aplicaciones, desafíos y oportunidades. Acceso IEEE, 7 , 117134–117151. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESO.2019.2936094

Pérez-Solà, C., Delgado-Segura, S., Herrera-Joancomartı, J., & Navarro-Arribas, G. (2019). Análisis de la adopción de SegWit en Bitcoin. URL: Https://Deic-Web. Uab. Gato/~ Guille/Publicaciones/Papeles/2018. Recsi. Segwit. Pdf (visitado el 13/06/2020). https://deic.uab.cat/~guille/files/papers/2018.recsi.segwit.pdf

Popper, N. (2015). Oro digital: la historia no contada de Bitcoin. Pingüino Reino Unido.

Schollmeier, R. (2001). Una definición de red peer-to-peer para la clasificación de arquitecturas y aplicaciones peer-to-peer. Actas de la Primera Conferencia Internacional sobre Computación Peer-to-Peer, 101–102. https://doi.org/10.1109/P2P.2001.990434

Ley Modelo de la CNUDMI sobre Firmas Electrónicas (2001) | Comisión de las Naciones Unidas para el Derecho Mercantil Internacional . (2001). https://uncitral.un.org/en/texts/ecommerce/modellaw/electronic_signatures

Wayner, P. (1996). Efectivo Digital: Comercio en la Red. Profesional AP.

Wright, CS (2008). Bitcoin: un sistema de efectivo electrónico de igual a igual. Revista Electrónica SSRN . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3440802

Wright, CS y Savanah, S. (2022). Determinación de un secreto común para el intercambio seguro de información y claves criptográficas jerárquicas y deterministas (patente de los Estados Unidos N.º US11349645B2). https://patents.google.com/patent/US11349645B2/en?assignee=nchain&before=priority:20160301

Digital Signatures …

Chief Scientist at nChain and inventor of Bitcoin and over 1000 other things.

Publicada el 6 de julio de 2022

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/digital-signatures-craig-s-wright/

Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending…

The Bitcoin White Paper notes the use of a digital signature algorithm and its need to prevent the deployment of trusted third parties or alternative systems. However, in BTC core, alternative systems have been developed, such as The Lightning Network (Antonopoulos et al., 2021) and with SegWit (Pérez-Solà et al., 2019), the requirement for a third-party has been reintroduced (Faltibà, 2018, p. 16).

As the sentence notes, digital signatures provide part of the solution. This aspect of bitcoin in itself is not new. Wayner (1996) documented multiple requirements for digital signatures (Wayner, 1996, p. 28) and digital signature algorithms (Wayner, 1996, p. 18) and multiple forms of digital or electronic cash over a decade before the launch of bitcoin. One solution from this time includes signature-only public key systems (Wayner, 1996, p. 17).

The use of signature-only public-key systems is defined in work by Wayner (1996, p. 17), noting that a system that can be used to verify a signature but that is not used in encrypting messages and hence “keeping them out of the eyes and ears of the police” can be created in a way that does not “tend(s) to annoy some governments that want to control the use of encryption”. Such systems differ from blinded digital signatures, which are used in creating anonymous cash (Wayner, 1996, p. 18). Bitcoin users a non-blinded signature system that is not encrypted. Minded signature systems have been aroundsince the 1980s.

As the second sentence of the whitepaper notes, digital signatures provide part of the solution. Many other aspects of bitcoin are required to make it secure and functioning. However, some of the benefits remain misunderstood. Primarily, bitcoin is a micro payment system. The system aims to provide the capability for electronic cash that can be distributed as “small casual transactions” (Wright, 2008, p. 1). However, for large value transactions, money-laundering and financial transaction rules require the use of intermediaries(Geiger & Wuensch, 2007).

Bryans (2014) noted how bitcoin requires anti-money laundering provisions and that AML enforcement requires that large value transactions (generally over USD 10,000) require reporting and intermediaries. These requirements are necessary for cash-based payments as well. So, the introduction of bitcoin doesn’t mitigate this requirement. As cash in its physical form can be used for money-laundering, the argument that bitcoin is different because it’s cash-like is nonsensical. Rather, bitcoin is cash-like and thus necessitates using the same existing rules as occur with cash transactions. The distinction is that bitcoin is completely traceable, and any transactions that are made for large values can easily be monitored and reported as per the original White Paper, “[a]ny needed rules and incentives can be enforced with this consensus mechanism” (Wright, 2008, p. 8).

What Is a Digital Signature

The various definitions and requirements related to electronic signatures and identities are documented in detail by Brazell(2018). (2014) In this work on electronic signatures and identities, the author documents the standards, technical requirements, identity issues and jurisdictional challenges associated with digital signatures. These definitions are provided in a global context. In the “new privacy model” (Wright, 2008, p. 6) provided by bitcoin, identities remain a necessary part of the solution. The distinction is that the public can see somebody sending information but cannot link it to anyone.

This privacy model does not remove the necessity for identity (Bryans, 2014). Rather, the new privacy model produced a bitcoin allows individuals to exchange identities where needed and to a level that is needed. For example, two individuals engaged in a small trade such as purchasing a coffee do not need to exchange large amounts of information. Instead, the coffee shop can provide information concerning the business identity in the form of an invoice, and the user can be treated as a person paying by cash. In this way, the transaction level dictates how much information must be exchanged, and none of this information must be put on-chain.

Signatures can always be repudiated (Brazell, 2018, p. 298). Repudiation or non-repudiation is not a technical issue, and the attempts to create non-repudiation through technical methodologies failed to understand the legal requirements (Brazell, 2018, p. 90). As Brazell (2018, pp. 90–91) notes in section 4-054;

- It is widely believed that a digital signature reduces the freedom of the signatory to repudiate an electronic signature on any grounds other than those equally available in respect of handwritten signatures, namely mistake, duress and the like. However, this is not the case because of the digital signature’s inability to identify the signatory. A digital signature only provides what a key was used to sign, not the circumstances under which it was used. This gap between signature and signatory leads to the need for legal assignment of responsibility for the consequences of signature, which is addressed in the UNCITRAL Model Law on electronic signatures. A biometric, on the other hand, may provide genuine non-reputability.

- Nevertheless, as this review shows digital signatures have no particular advantage over other forms of electronic signature in respect of many of the functions for which a handwritten signature is used, and in particular, are significantly flawed when it comes to the function of identifying the signatory with confidence. In order to produce an electronic signature which can perform all the functions of a handwritten signature, a combination of biometric and digital signature technology is required.

Bitcoin can function as cash, small incontestable values where the cost of seeking to repudiate the transaction exceeds the value of the amount exchanged compared to the amount needed to go to court and contest the exchange. In this, transactions within bitcoin. In amounts under $10,000, there will be little possibility of recovering funds in any meaningful way. Even in Small Claims Court, the recovery cost will exceed any benefit gained in seeking a court order to recover money distributed across bitcoin. Conversely, for large amounts, it is possible to create a strategy that alerts nodes to reject blocks that have been frozen by court order.

“One such strategy to protect against this would be to accept alerts from network nodes when they detect an invalid block, prompting the user’s software to download the full block and alerted transactions to confirm the inconsistency” (Wright, 2008, p. 5). For example, creating a block that implements and allows a transaction from a frozen UTXO would be considered invalid. This process can be automated, allowing nodes to easily take action against criminal funds or money that has been seized through a court order.

Such a process would be completed in two parts with the freezing and then the reallocation of funds. However, as noted above (Brazell, 2018), non-repudiation is not something that is all possible in electronic systems and remains something that is legally required to be reversible through court-based processes. Importantly, bitcoin White Paper does not note that the system protects possession but rather that it protects “ownership”.

The main benefits being discussed in the bitcoin whitepaper are related to the use of the system is electronic cash. However, when there are third parties, the system requires a means of managing access and uses that is more expensive than can be delivered in bitcoin. In this, rather than having an electronic cash system, “small casual payments”, we end up with a digital gold system that is expensive and less effective than banks and the existing financial infrastructure. The Holy Grail of the Internet was always digital cash (Wayner, 1996). The distinction with bitcoin is that rather than creating an untraceable anonymous system such as eCash (Chaum, 1983), bitcoin created a private or pseudonymous system that maintains end and traceability.

The distinction between these ideas is in creating a Cryptocurrency as in eCash against digital cash, or an electronic cash system is exemplified in bitcoin. Bitcoin is private and pseudonymous. However, this does not mitigate the need for identity. Brazell (2018, pp. 37–62) documents the requirements for identity and its reference to digital signatures. The key aspect of bitcoin that many people forget or fail to understand is that a digital signature requires an identity.

The UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Signatures (2001) was the foundation for much of the digital signature legislation enacted worldwide, including that within the USA and UK. The European provisions also follow the model Law. In each instance, it is important to note that a key function of a signature includes “identifying the author or sender of a document” (Brazell, 2018, p. 15). So, the use of digital signatures is not merely referred to as the use of a digital signature algorithm. A digital signature algorithm is a technological system that provides the capability to create a digital signature but is not in itself a digital signature.

To be a digital signature still requires an identity. For high-end and high-value transactions, identity can be provided through certification authorities and PKI (Hunt, 2001). However, for low-value transactions, it becomes possible to create a web of trust (Caronni, 2000) where detailed information about individuals is not required, or partial identities are exchanged (Brazell, 2018, pp. 39–40). The use of full or partial identities will be predicated on the size of the transaction and the necessity of the exchange of identity information for the particular scenario.

As Caronni (2000) observed, a web of trust allows a user of the system to choose for him or herself who that individual deems to be trustworthy. In the exchange of small value casual transactions, the ability to create an irreversible exchange is important. If an individual purchases a small value item, the individual can still request a refund and negotiate this as per cash. The interactions derived from individuals using electronic cash do not change significantly from physical cash.

In this sentence of the White Paper, the requirement is to create a digital signature system. In this, keys may be derived using the homomorphic properties of ECDSA that allow for a subkey to be created (Wright & Savanah, 2022). Such a system maintains identity but also makes the broadcast of keys across the Blockchain network publicly traceable while not directly linked to the individual’s identity publicly. As such, traceability remains, but equally small casual transactions can be hidden from the world.

The benefits defined within the bitcoin White Paper are related to the ability to minimise the transaction size. That is electronic cash and micro payments. Bitcoin has been falsely promoted as digital gold (Popper, 2015), yet, the reality is that the system holds no such properties. Bitcoin scales and has value as a payment system that solves the key problems with digital cash and Electronic Commerce (Wayner, 1996) that have been discussed for decades. However, Bitcoin can be expensive unless the transaction volume is maintained at a high rate. The trade-off is the number of nodes versus the type of system.

However, the bitcoin White Paper does not mention decentralization. The paper notes in section 2 (Wright, 2008, p. 2) that “[a] common solution is to introduce a trusted central authority, or mint, that checks every transaction for double-spending”. Bitcoin removed the need for a central issuing authority by automating the process. All bitcoin tokens were issued in January 2009. The single issue was coupled with an automated distribution process in this process. This removed the necessity to have a single trusted central authority or mint. Rather, a plurality of competing organisations audit and check one another.

On top of this, any user of the system can view and audit transactions (Monrat et al., 2019). More importantly, in sending transactions between one another, individuals such as Alice and Bob can individually validate their own transactions and maintain evidence of any alteration or change. This aspect is an important part of bitcoin. The SPV functions of bitcoin allow individuals to check and maintain the number of tokens they own, validate them, and ensure that nothing has been altered.

When Alice wants to transmit information to Bob, she can check her own set of tokens and ensure these are valid without changes. Bob can do the same thing when Alice hands him the transaction. The ability to trace transactions on the Blockchain allows Bob to validate the input transaction from Alice without maintaining a full copy of the Bitcoin Blockchain. The SPV functions of bitcoin allow him to validate Alice’s transaction against the Merkle path and the hashed block headers. If anything changes in the block hash headers, then all system users will be alerted and know that something has been altered. They can do this without maintaining a full copy of the Blockchain.

When the White Paper states that digital signatures provide part of the solution, this refers to the first sentence that details a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash. That was explained in the previous article. As the first sentence notes, the requirement is that payments are sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. As this is a “purely peer-to-peer” (Schollmeier, 2001) version of electronic cash, the requirement is direct communication between the parties and not communication via nodes.

For this to work, the solution must work by having Alice send communications directly to Bob over the IP to IP exchange methodologies built into bitcoin and the early days. While BTC and other systems have removed IP to IP exchanges, this also removes the decentralised aspect of bitcoin. Bitcoin is not decentralised because of nodes. Bitcoin is decentralised because individuals can directly communicate without using nodes for the exchange. In this series of communications, Alice and Bob can exchange and negotiate extensively, only settling the final transaction on-chain.

In this process, they can create invoices and purchase orders and save hashes of these documents that demonstrate the exchange of information between the two parties without this information ever going on-chain. Alice and Bob can prove their identity to each other while maintaining all this information off-chain and ensuring they follow the “new privacy model” advocated within bitcoin (Wright, 2008, p. 6).

Bitcoin provides a solution to the provision of electronic cash and payments from one party to the other without using a financial institution. Electronic cash isn’t a system that should be designed to transfer millions of dollars without any supporting evidence. Just as cash requires additional information to be exchanged and AML provisioning to be conducted, electronic cash follows the same regulations. Bitcoin simplifies this process by automating many of the exchanges. This does not make an anonymous system; it makes a private or pseudonymous with the information concerning the exchange is not public. However, just because the information is not public does not mean it does not exist.

Conclusion

Digital signatures require a digital signature algorithm such as ECDSA and an ability to exchange identity. The exchange of identity-based information can be done in bitcoin using the homomorphic properties of ECDSA so that keys can be provably linked to an identity key while remaining private (Wright & Savanah, 2022). As the system notes, traditional electronic cash systems based on digital signatures have required the use of a trusted third-party or, as this is alternatively referred to, a payment intermediary. Bitcoin removes this requirement by having a distributed competitive system of nodes that act as a time stamping server.

These nodes are not the primary methodology for disseminating and distributing transactions. Rather, the nodes timestamp an index the exchanges done directly between Bob and Alice. Rather than having a trusted third-party, bitcoin utilises a competitive system where corporate entities running nodes attempt to find solutions to problems faster than their competition and earn more money. Together, digital signatures enable Bob and Alice to securely exchange value while the node network indexes the transactions using an automated process that ensures the double-spent transactions are quickly alerted throughout the network.

References

Antonopoulos, A. M., Osuntokun, O., & Pickhardt, R. (2021). Mastering the lightning network: A second layer blockchain protocol for instant bitcoin payments. O’Reilly.

Brazell, L. (2018). Electronic Signatures and Identities: Law and Regulation. Sweet & Maxwell.

Bryans, D. (2014). Bitcoin and Money Laundering: Mining for an Effective Solution Note. Indiana Law Journal, 89(1), 441–472.

Caronni, G. (2000). Walking the Web of trust. Proceedings IEEE 9th International Workshops on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises (WET ICE 2000), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1109/ENABL.2000.883720

Chaum, D. (1983). Blind signatures for untraceable payments. Advances in Cryptology, 199–203.

Faltibà, Z. (2018). The Lightning Network—Striking clarity on third millennium economy. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.25320.01283

Geiger, H., & Wuensch, O. (2007). The fight against money laundering: An economic analysis of a cost‐benefit paradoxon. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 10(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/13685200710721881

Hunt, R. (2001). PKI and digital certification infrastructure. Proceedings. Ninth IEEE International Conference on Networks, ICON 2001., 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICON.2001.962346

Monrat, A. A., Schelén, O., & Andersson, K. (2019). A Survey of Blockchain From the Perspectives of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access, 7, 117134–117151. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2936094

Pérez-Solà, C., Delgado-Segura, S., Herrera-Joancomartı, J., & Navarro-Arribas, G. (2019). Analysis of the SegWit adoption in Bitcoin. URL: Https://Deic-Web. Uab. Cat/~ Guille/Publications/Papers/2018. Recsi. Segwit. Pdf (Visited on 06/13/2020). https://deic.uab.cat/~guille/files/papers/2018.recsi.segwit.pdf

Popper, N. (2015). Digital Gold: The Untold Story of Bitcoin. Penguin UK.

Schollmeier, R. (2001). A definition of peer-to-peer networking for the classification of peer-to-peer architectures and applications. Proceedings First International Conference on Peer-to-Peer Computing, 101–102. https://doi.org/10.1109/P2P.2001.990434

UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Signatures (2001) | United Nations Commission On International Trade Law. (2001). https://uncitral.un.org/en/texts/ecommerce/modellaw/electronic_signatures

Wayner, P. (1996). Digital Cash: Commerce on the Net. AP Professional.

Wright, C. S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3440802

Wright, C. S., & Savanah, S. (2022). Determining a common secret for the secure exchange of information and hierarchical, deterministic cryptographic keys (United States Patent No. US11349645B2). https://patents.google.com/patent/US11349645B2/en?assignee=nchain&before=priority:20160301

Dejar un comentario

¿Quieres unirte a la conversación?Siéntete libre de contribuir!